Each morning since we’ve been cruising, I’ve been woken by dogs.

Around 3.00am, they start. Howling. Barking. Deep barks. Light barks. Happy barks. All kinds. It’s not aggressive, just… communal. A chorus. Maybe they sense the coming call to prayer, or maybe this is simply how they greet the day. Oddly, it’s comforting.

Then come the prayers.

This morning in Aswan, they were gentler than Esna. Still present, but softer. The city easing itself awake.

I rose around 6.00am, showered, and headed to breakfast at 7.00am.

Today, Mardi and I split up. Just for the day.

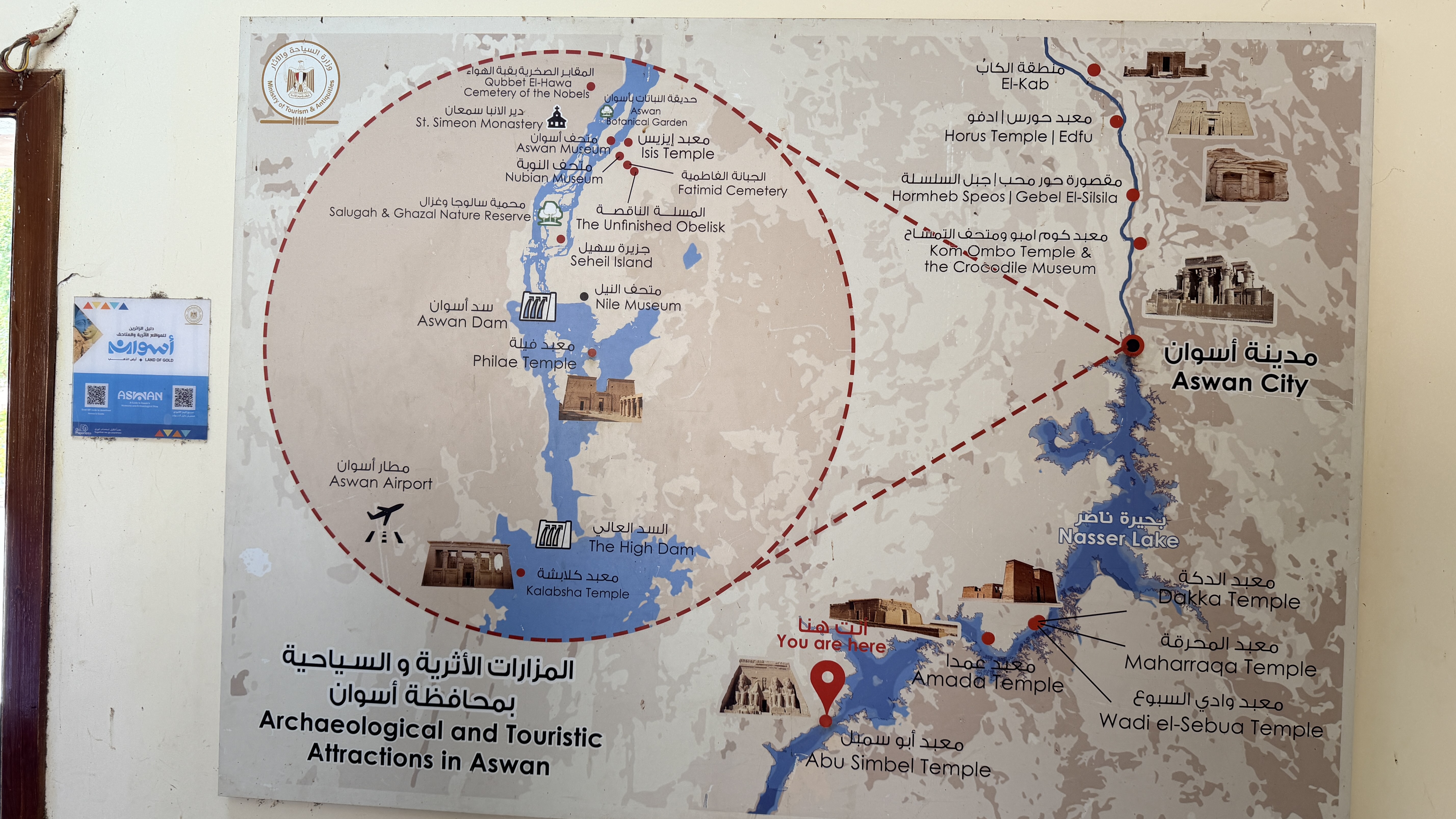

I was heading south to Abu Simbel with David and Kerrie. Mardi opted for a gentler day: markets, river sailing, and afternoon tea at the Old Cataract Hotel, made famous by Agatha Christie’s Death on the Nile.

A quick note on the word cataract: it has nothing to do with eyes. In Nile terminology, a cataract refers to rocky rapids—sections where granite outcrops disrupt the river’s flow. These cataracts historically marked natural boundaries and were central to the engineering challenges addressed by the Aswan High Dam.

The Aswan High Dam and Lake Nasser

After breakfast, we boarded our bus for a visit to the Aswan High Dam, followed by a flight to Abu Simbel.

The dam is vast in every sense:

4 kilometres long 1 kilometre wide at the base 45 metres wide at the top 111 metres high Built as a rock-fill dam, using an estimated 17 times the stone used in the Great Pyramid of Giza

Completed in 1970, the dam controls flooding, provides hydroelectric power, and created Lake Nasser, one of the largest artificial lakes in the world. Lake Nasser covers roughly 5,250 square kilometres, making it slightly larger than Kangaroo Island and not far off the size of Tasmania’s West Coast region.

Flying over it drives home the scale. From the air, it looks endless. A shimmering inland sea carved into desert.

Arrival at Abu Simbel

We landed and within minutes arrived at Abu Simbel. Our guide for the day, Rasha, briefed us in the welcome hall. Guides aren’t permitted inside the temples, so she carefully explained the layout and how best to experience them.

Most guests chose to walk. David, Kerrie, and I happily paid US$2 for a golf cart. It was hot, dusty, and uneven underfoot. Best two dollars of the day.

Four minutes later, we rounded the bend and stopped.

And there it was.

The Great Temple of Ramesses II

Carved directly into the mountainside, the Great Temple of Ramesses II dominates the landscape. Four colossal seated statues guard the entrance, each around 20 metres tall. All of Ramesses II. He liked himself a lot.

From left to right:

Ramesses II, intact and commanding Ramesses II, damaged—his upper body destroyed by an ancient earthquake Ramesses II, perfectly preserved Ramesses II, equally imposing

Flanking the legs of these giants are smaller statues of queens, princes, and princesses, reminding you exactly who stands at the centre of this story.

We stood in silence for a few moments, still some distance away, trying to absorb the scale. Even at 100 metres, it fills your vision.

Inside, the experience deepens.

The temple is carved straight into the rock with astonishing precision. No margins for error. Every surface is decorated: columns, walls, ceilings. Scenes of banquets. Gods feasting. Ramesses II in battle, smiting enemies with theatrical certainty. The narrative scrolls past as you move deeper inside.

The inner sanctuary holds statues of Ra-Horakhty, Amun-Ra, Ptah, and Ramesses II himself, elevated to divine status.

The craftsmanship is extraordinary. It feels intentional, confident, eternal.

Nefertari’s Temple

Nearby stands the Temple of Queen Nefertari, dedicated to Hathor, goddess of love and joy.

It is rare—almost unheard of—for a queen to be honoured with a temple nearly equal in scale to a king’s. Ramesses II was deeply devoted to Nefertari, and this temple reflects that.

The façade features six statues, four of Ramesses and two of Nefertari, all equal in height—a remarkable statement in ancient Egypt. Inside, the reliefs mirror those next door: rituals, gods, and scenes of royal life, carved with exquisite balance and grace.

Engineering Marvels, Ancient and Modern

Abu Simbel represents two feats of engineering.

The first was its original construction in the 13th century BCE, carved directly from solid rock with perfect symmetry and alignment, oriented precisely to the sun.

The second came in the 1960s, when the rising waters of Lake Nasser threatened to submerge the temples. Between 1964 and 1968, the entire complex was cut into more than 1,000 blocks, each weighing up to 30 tonnes, and reassembled 65 metres higher and 200 metres back from the river.

It remains one of the greatest archaeological rescue operations ever undertaken.

Twice a year—around 21 February and 21 October—sunlight penetrates the inner sanctuary, illuminating all statues except Ptah, god of the underworld, who remains in shadow. Scholars believe these dates mark Ramesses II’s birthday and coronation.

Precision layered upon precision.

Back to Aswan and a Night at the Old Cataract

We returned to Aswan by bus and short flight, exhilarated and exhausted.

That evening, Viking arranged transport to the Old Cataract Hotel, an icon of Victorian and Edwardian colonial architecture, originally opened in 1899 and expanded in the early 20th century. Its grand arches, high ceilings, shaded verandas, and river-facing terraces reflect European elegance adapted to the Nile.

We began with drinks in the bar—eye-wateringly expensive but worth it for the setting—before being guided through long corridors lined with photographs of former guests: Omar Sharif, Princess Diana, Agatha Christie, and many others.

Dinner at the 1902 Restaurant was outstanding. Steak. Veal. Lamb. Chocolate lava cake. Crème brûlée. A sense of stepping back a century lingered throughout the meal.

We wandered the grounds afterward, soaking in the atmosphere, before returning to the ship.

Tomorrow, we turn north again, the Nile carrying us back toward Luxor.

Another chapter closes. Another opens.