23 January

Today everything we’ve seen over the past week finally came together.

We started the morning with breakfast in the restaurant and, for once, what felt like a leisurely start. An 8.00am departure. After days of 4.00am alarms, it honestly felt like the middle of the day. I’d already been awake since 4.00am for a job interview, and after it wrapped up I managed to crawl back into bed for a couple of hours. Not ideal, but manageable.

Today was always going to be big.

We’ve spent days looking at statues, artefacts, coffins, masks, and treasures. Especially those of Tutankhamun. Today we were finally going to see where they came from. Where kings were actually buried. Hidden. Protected. Forgotten. And then rediscovered.

The Valley of the Kings came into being around 1,000 years after the pyramids were built. The Egyptians eventually realised that massive monuments were effectively signposts advertising unimaginable wealth below ground. Of the roughly 128 pyramids built, almost all were looted, vandalised, or stripped bare. It took centuries, but the lesson finally landed: hide the dead.

So the kings were buried here. In isolated valleys. Beneath mountains. Their tombs cut deep into rock, invisible from above. Common people were buried elsewhere, often in simple shafts. But royal tombs were something else entirely.

We reached the valley about 20 minutes after leaving the ship. The car park was already heaving. Buses. Minivans. Taxis. A steady stream of people funnelled towards the entrance. Ibrahim gathered us, explained what lay ahead, and promised that today would somehow top everything we’d seen so far.

He wasn’t wrong.

After security, we boarded electric shuttle carts, oversized golf buggies carrying 14–20 people, and were whisked a few hundred metres into the heart of the valley. There, Ibrahim gave us final instructions.

That’s when I realised I’d lost my ticket.

Pocket. Nothing. Other pocket. Nothing. Just lint.

I told Ibrahim. He apologised but explained I’d need to go back and buy another ticket. My heart sank. This was the thing I’d been waiting for. Fortunately, between the four of us, we had enough shared entries to get me through. Crisis averted, but my heart rate took a while to settle.

Tomb of Ramesses IV (KV2)

Our first descent was into the tomb of Ramesses IV, a 20th Dynasty pharaoh. Modern steps lead you down into the entrance, then wooden walkways take over. The descent is relatively short, but immediately overwhelming.

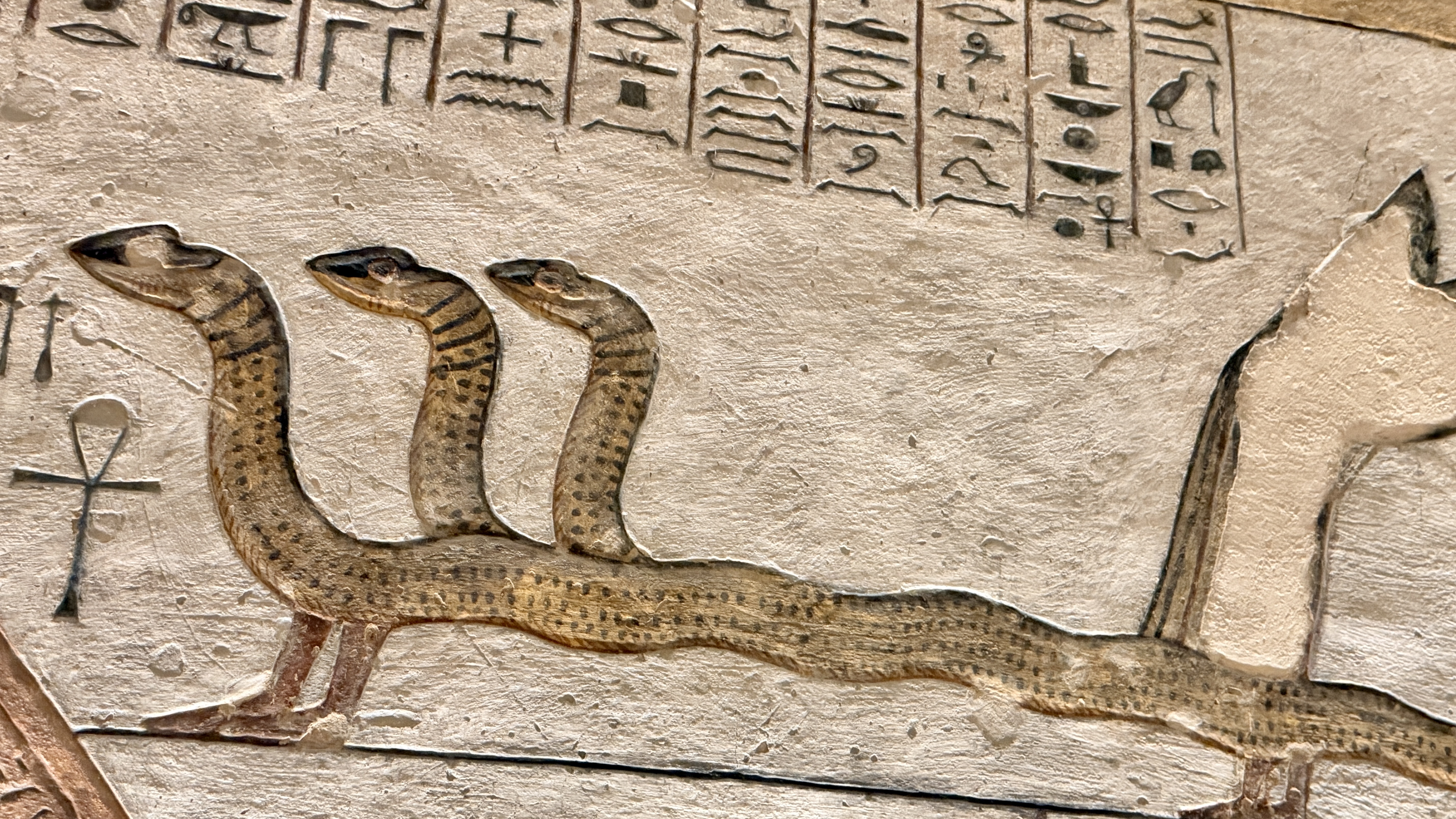

Every surface is covered. Walls. Ceilings. Columns. Vivid paintings depicting the afterlife: gods with animal heads, serpents, owls, crocodiles, three-headed creatures, and scenes of daily life interwoven with cosmic journeys. Boats crossing the underworld. Deities guiding the king.

The temperature rises quickly as you descend. The air thickens. People crowd in, phones raised, trying to capture everything at once. It’s impossible. There’s too much. Even the ceilings are alive with imagery.

At the base are several chambers, remarkably preserved thanks to the dry desert climate. Standing there, underground, surrounded by colour and symbolism created over 3,000 years ago, it’s hard to process what human hands achieved in darkness, by torchlight, for a king they believed would live forever.

How the ancient Egyptians understood the world

The tomb art isn’t decoration. It’s instruction.

The ancient Egyptians believed the world was created from a chaotic primeval ocean called Nun. From it rose the first mound of earth, and from that came the gods. The sun god Ra travelled across the sky by day and through the underworld by night, battling chaos to rise again each morning. Death wasn’t an end, but a transformation.

The afterlife required knowledge. Spells. Maps. Guidance. The tombs are manuals for eternity, explaining how the king would navigate the underworld, defeat dangers, and be reborn with the sun.

In many ways, it’s not so different from today. We’re still trying to explain where we came from, what happens when we die, and how to make sense of the world. The Egyptians were just far more comfortable admitting they didn’t have all the answers.

We emerged back into the heat. The cool air hit our faces. Outside it was already around 28 degrees. Underground, it felt far hotter.

More info: Ramesses IV (KV2)

Ramesses IV ruled during the 20th Dynasty (c. 1155–1149 BCE). His tomb is simpler in layout compared to earlier New Kingdom tombs, reflecting the declining economic and political power of Egypt at the time. The tomb follows a relatively straight axis and was completed quickly, likely due to the short length of his reign.

Despite its simplicity, the tomb is well decorated and contains vivid astronomical ceilings and religious scenes focused on the sun god Ra. The emphasis is less on artistic innovation and more on reaffirming traditional religious texts, suggesting a period of consolidation rather than expansion or ambition.

Tomb of Tutankhamun (KV62)

Next was the tomb of Tutankhamun, the boy king. Discovered almost intact in 1922 by Howard Carter, his burial goods stunned the world. Yet the tomb itself tells a very different story.

It’s small. Plain. Painted rather than carved. The shaft is short and direct. The artwork feels rushed. And that’s because it was.

Tutankhamun died suddenly at around 18 or 19, likely from complications after breaking his leg and developing an infection. There was no time for a grand tomb. He was buried quickly, using what space and preparation existed.

Inside, there are two main chambers. To the right is the sarcophagus. To the left, the king lies in state. His mummy is visible. Small. Withered. Over 3,300 years old. Wrapped from neck to ankles, but his face, hair, feet, toes, and toenails clearly visible.

Standing there, looking at him, I couldn’t help wondering what he would think if the afterlife truly exists and he knows we’re here, staring back at him.

More info: Tutankhamun (KV62)

Tutankhamun ruled Egypt during the 18th Dynasty (c. 1332–1323 BCE). Although his reign was short and politically modest, his tomb is the most famous in the Valley of the Kings because it was discovered largely intact in 1922 by Howard Carter. The tomb itself is relatively small, likely because Tutankhamun died unexpectedly at around 18 or 19 years of age. Despite its size, the burial goods were extraordinary, including nested coffins, a solid gold funerary mask, chariots, furniture, weapons, jewellery, and ritual objects intended for the afterlife.

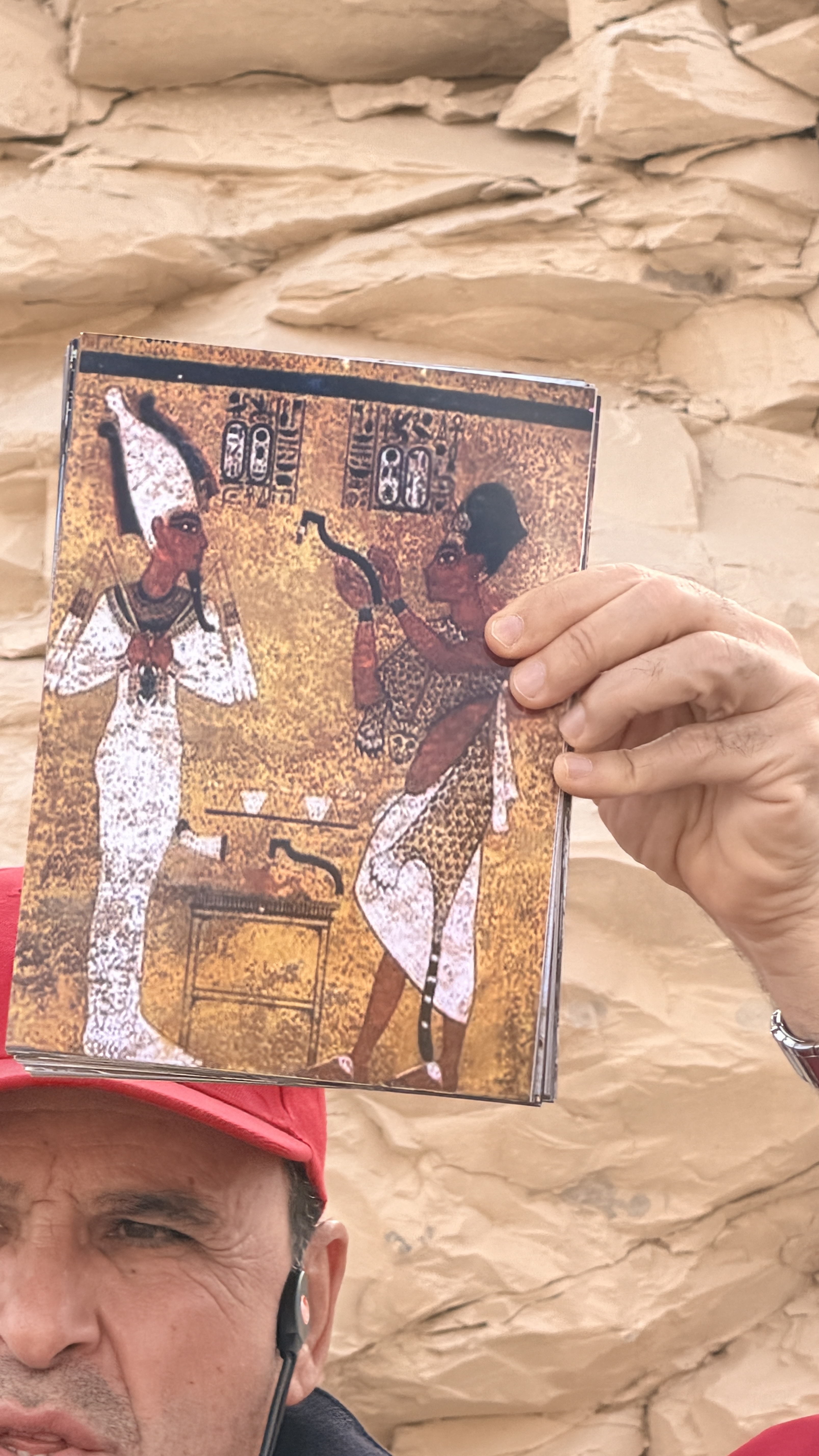

The wall paintings in Tutankhamun’s burial chamber are simple compared to other royal tombs, but highly symbolic. They depict his journey into the afterlife, his acceptance by the gods, and his transformation into Osiris, god of the dead. His tomb provides unparalleled insight into royal burial practices of the New Kingdom and has shaped modern understanding of ancient Egypt more than any other single discovery.

Tomb of Seti I (KV17)

Then came Seti I.

If Tutankhamun’s tomb is famous, Seti’s is magnificent.

The descent is long and steep. Around 45 degrees at first, then continuing deeper and deeper. This tomb had time. Resources. Care. The walls are carved, not painted, then filled with rich colour. The scenes are elaborate, layered, and precise.

We saw rabbits, crocodiles, human figures with animal limbs, serpents, gods, and detailed journeys through the underworld. The craftsmanship is astonishing. Even after 3,200 years, the colours remain vivid.

David and I lingered. Others moved on. I stood still, absorbing it, remembering Howard Carter’s words: “Yes, wonderful things.” That’s exactly what this is.

More info: Seti I (KV17)

Seti I, father of Ramesses II, ruled during the 19th Dynasty (c. 1290–1279 BCE) and is widely regarded as one of Egypt’s most capable and respected pharaohs. His tomb in the Valley of the Kings is considered one of the finest ever constructed. It is exceptionally long, deep, and richly decorated, extending over 130 metres into the rock.

The wall reliefs and paintings in Seti I’s tomb are among the most detailed and beautifully preserved in the valley. They include extensive religious texts such as the Book of the Dead, Book of Gates, and Amduat, all guiding the pharaoh through the underworld. The craftsmanship, colour, and precision reflect the peak of New Kingdom tomb design and religious belief.

Tomb of Ramesses V and VI (KV9 – the “bent shaft” tomb)

We then descended into the tomb often described as having a bent or angled axis, KV9, originally begun for Ramesses V and later expanded by Ramesses VI.

This tomb goes down, down, down. The heat rises again. The decorations are different in style to Seti’s, less refined perhaps, but no less impressive. Astronomical ceilings. Religious texts. Long corridors telling the story of the sun’s journey through the night.

We paid extra to access additional chambers here, something not included in the standard ticket. These rooms added further layers to the story, reinforcing how obsessed the Egyptians were with ensuring safe passage to the afterlife.

By now, we were drenched in sweat. Four tombs in two hours. And yet, I could have stayed all day. All week. This place is spellbinding.

More info: The “Bent Shaft” Tomb – Ramesses V and Ramesses VI (KV9)

The tomb often described as having a bent or angled axis is KV9, originally begun for Ramesses V and later expanded and reused by his successor Ramesses VI. The change in direction partway through the tomb reflects both practical constraints and evolving tomb design during the late New Kingdom.

KV9 is notable for its richly decorated corridors and ceilings, including detailed astronomical scenes showing the sun’s journey through the underworld. The tomb is large, heavily inscribed, and demonstrates how later pharaohs reused and adapted existing tombs due to time pressures, security concerns, and resource limitations

Temple of Hatshepsut (Deir el-Bahri)

The hits kept coming.

We visited the mortuary temple of Hatshepsut, one of the most extraordinary rulers in Egyptian history and the only woman to rule Egypt as a pharaoh in her own right. Even 3,000 years ago, the patriarchy was firmly entrenched, and Hatshepsut navigated it by presenting herself as male in statues and reliefs.

Her temple is unlike anything else. Built into the cliff face at Deir el-Bahri, it unfolds across three vast terraces, connected by ramps, lined with hundreds of columns. The symmetry. The scale. The ambition. It was built to last for eternity, and it nearly has.

More info: Hatshepsut

Hatshepsut ruled during the 18th Dynasty (c. 1479–1458 BCE) and is one of ancient Egypt’s most successful and remarkable pharaohs. Although female, she ruled as a full king rather than as a regent, adopting traditional male royal titles and iconography. In statues and reliefs, she is often depicted with a false beard and masculine body proportions, reinforcing her legitimacy in a male-dominated political system.

Her reign was marked by peace, prosperity, and extensive building projects, rather than military conquest. She is best known for commissioning the magnificent mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri, near the Valley of the Kings, and for organising a famous trading expedition to the Land of Punt, which brought wealth, incense, exotic animals, and plants back to Egypt. After her death, many of her images and names were deliberately erased, likely by her successor Thutmose III, but modern archaeology has restored her reputation as one of Egypt’s most capable and visionary rulers.

Howard Carter’s House

We also visited Howard Carter’s house, the modest mud-brick home where he lived while searching for Tutankhamun’s tomb. Simple rooms. A small study. Sparse furnishings. Designed to keep heat out in summer and warmth in during winter.

It speaks volumes about the man. Patient. Dedicated. Obsessed. Without him, so much of what we’ve seen would still be hidden.

Colossi of Memnon

Our final stop was the Colossi of Memnon, two massive seated statues standing alone in a field. Once part of a grand mortuary temple, everything else has vanished. These remain. Cracked. Damaged. Barely standing. Yet still imposing.

They are another reminder of Egypt’s obsession with eternity and the gods.

Back to the river

We returned to the ship exhausted but exhilarated. The story is coming together now. We started with monuments 4,500 years old and are gradually moving forward through time as we travel south into Upper Egypt, seeing how cultures overlapped, changed, and influenced one another.

For the first time on this trip, we had nothing scheduled in the afternoon.

At around 1.30pm, the ship set sail. We ate lunch, then spent the afternoon reading, chatting, blogging, editing photos, and watching Egypt slide past from the deck. The Nile is alive. Boats. Villages. People. Children waving. Our captain loves the horn, sounding it every few seconds as ships pass, sometimes four abreast.

We entered the Esna Lock, barely a metre wider than the ship on each side. Sellers in small boats clustered around us, shouting and waving wares. Then the gates closed. The ship rose about 22 feet. Minutes later, we were released back into the Nile and docked at Esna.

That evening we attended the Viking welcome and toast, followed by a briefing on tomorrow’s activities in Esna. Dinner followed, and quiet conversation about what we’d just experienced.

After eight days, the pace finally slowed.

But the journey through time is far from over.